Stream Restoration at the Confluence of a Sacred Past and a Promised Future

Looking out over Galena Soónkhani Nature Preserve.

Nestled between Utah’s urban Jordan River and a busy highway, Galena Soónkahni Nature Preserve is an unexpected wetland haven. Development sprawls on the edges of the wetland. Across the street, a commuter train delivers passengers to the heart of Draper, a bustling city in the western foothills of the Wasatch Mountains.

Despite its constant hum of city sounds, this 250-acre preserve has a unique history as a gathering space for Indigenous communities for at least 3,000 years. Protected by a conservation easement since 2007, the preserve holds the quiet of nature and deep cultural history in perpetuity. But more work is needed to bring the surrounding wetlands back to life.

Galena Soónkahni

Volunteers and partners gather creekside for a restoration demo.

I’m here today with a group to restore the streams and wetlands at this unique location, which represents a rare bastion of open space along the Jordan River. Volunteers, nonprofit partners from Sageland Collaborative and Utah Open Lands, and state employees are restoring Corner Canyon Creek, which feeds into the Jordan River in the heart of this preserve. We will remove invasive species, plant native seeds, and build beaver dam analogs (BDAs).

To the untrained eye, this location seems out of place compared with other beaver-based restoration sites. We park in a narrow gravel lot alongside the highway to meet volunteers and partners. From this vantage–and nearly any location throughout the surrounding urban area–the creek is invisible. I hear a volunteer quietly wonder why we are restoring such an urbanized site. Surrounded by all this developed space, what could be gained?

We experience the answer first viscerally as we drive down into the preserve. Sagebrush and rabbitbrush dot the landscape, reaching tall and wide for the rays of sun on this chilly October morning. The dirt road leads us past an old grain silo and follows the Jordan River Trail to the Soónkahni Monument. Surrounded by so much open space, I take a breath of fresh air and imagine what the valley looked like prior to European settlement.

The Soónkahni Monument features a sundial surrounded by eight pedestals that represent and pay tribute to the tribal nations that utilized this area historically and remain active members of our community - the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, the Navajo Nation, the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, the San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe, the Ute Indian Tribe, the Ute Mountain Tribe, and the Skull Valley Band of Goshute.

The Soónkahni Monument which features eight pedestals representing the tribal nations that have historically utilized this area.

Brad Parry, Vice Chairman of the Northwest Band of the Shoshone Nation, provides context about what Galena Soónkhani means to the Tribe. This site, and surrounding Draper City, represents the southern extent of the Tribe’s aboriginal territory. “Soónkahni means home. Wherever you see ‘Kahni’ in our language, that means home, and we want people to feel at home,” says Parry. “Any time you can restore something and make it feel like home, that’s the goal and that’s our goal as a Tribe.” He shares the importance of restoring sites like this for all beings.

Parry sees a big role for the entire community to join in restoration efforts. “The site is Indigenous, but look at all the people who live here now. We can work together as a community to restore what was there. As community members gather and participate in restoration activities, we hope Galena Soónkahni preserve can become a place to reflect on the beauty of nature, history, and what it means to be human. It’s important to spend time in nature and remember that we haven’t always been this fast-paced.”

The Northwest Band of the Shoshone Nation is currently leading a similar restoration project at Wuda Ogwa, the site of the January 1863 Bear River Massacre. Parry expands on the importance of this project,

“Culturally we have taken so much away from the earth, and it's time to start giving back. Beaver dam analogs improve water quality and help make our rivers more resilient to climate change. This is what we need to do right now. We believe that the Creator doesn’t want us to change the landscape in the ways we see now.

At Wuda Ogwa, groups are restoring the site to what it would have represented prior to contact with European settlers. We joke about using technology like pipes and human-made structures not being ‘natural,’ but sometimes Mother Nature, especially now, needs assistance from technology to make it better. We don’t always have to take, we now have an opportunity to give back.”

Protected Land

Before our group gets to work restoring the Galena site, we learn a bit more about the site’s ecological history. Stream ecologist Rose Smith encourages us to look across the wide, dry expanse of low-lying shrubs and grasses and imagine the lush, green floodplain that was here before. Today, the creek cuts through the floodplain toward the Jordan River just to the west in a deep, narrow channel, leaving nearby soils high and dry. The area covered by dry soil and shrubs likely supported a vibrant floodplain habitat in the past, providing food and shelter for wildlife and humans alike.

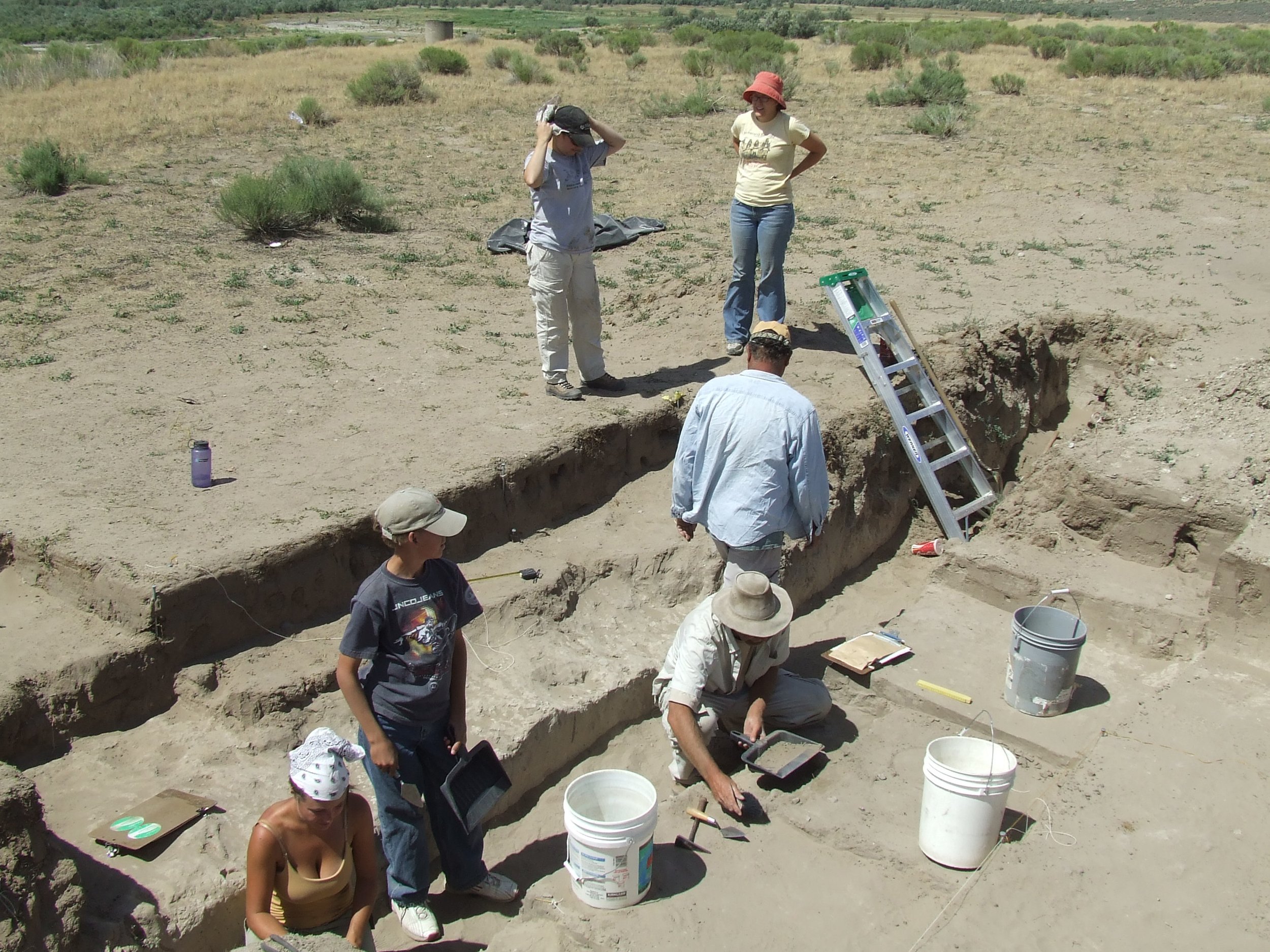

According to the site’s management plan, members of the Desert Archaic Culture are the oldest known inhabitants to this region, hunting, fishing and gathering food along the Jordan River between 10,000 B.C and 400 A.D. The Fremont Culture followed, bringing a combination of hunting and agricultural practices to the region for 1,500 years before the Ute, Shoshone, and Paiute tribes used the area. These tribes were present when European settlers arrived and transformed the floodplain for agriculture and grazing.

Now fragmented by urbanization, the floodplain has dried out. Plants that are more tolerant to dry, disturbed conditions have moved into the formerly wetted floodplain, signaling a reduction in habitat for wetland plants, birds, and other wildlife. However, this land is now protected and slated for a major restoration project that will reconnect the land to its historical ecological significance.

Especially in the arid west, floodplain wetlands are important for wildlife. However, the need for urban flood control and water use make these habitats extremely rare within cities. How then did the Galena Soónkahni Nature Preserve become the protected oasis that it is today?

Emily Ingram, Director of Conservation at Utah Open Lands, explains their organization’s role as a land trust in the protection of this site:

“In the early 2000s, the site was threatened by road, transportation, and industrial development. During that initial development process, they discovered some really unique archaeological artifacts. That was the catalyst for this whole conversation, that is, what is this land, what is the history, and how can we protect it in perpetuity?”

Artifacts discovered at the Galena Soónkahni tell a captivating story of human inhabitation over thousands of years. According to an in-depth report on the archaeological findings (Yentusch et al. 2009), the site was used intensively by the Desert Archaic people for up to 1,500 years. This site is quite special and rare given the highly mobile, hunter-gatherer nature of Archaic society, who are known to have covered large areas following seasonality of food sources. Based on the tools and other artifacts found, the site was likely occupied repeatedly for months or seasons at a time as a ‘base camp’ where people repaired tools, traded, and processed foods and hunted or gathered elsewhere.

Chemical signals left on stone tools used for cooking provide a glimpse into both the diet and seasonality of the Archaic people’s occupation of the Galena Soónkahni site. Native plants (including Sego lily, Cattail, Sunflower, Prickly pear, Osha root, Ryegrass, Barley, Sumac, and Yucca) were likely harvested and cooked on-site in early spring. Animal food sources include bison, deer, pronghorn, turtle, goose, and crane. There is also some surprising evidence of domesticated plants – beans, maize and squash cooked on site between 2,400 and 3,000 years ago– long before these species were thought to have arrived in the area (Yentusch et al. 2009).

As the history of this land was brought to public attention, Ingram tells us that Utah Open Lands’ Executive Director Wendy Fisher rallied the community and worked with our state legislature to get a conservation easement for the land. A conservation easement ensures that the property is protected in perpetuity, meaning that it will never be developed, mined, or altered from the state it was in when put under protection.

These protections ensure that the archaeological and ecological significance of this site can remain undisturbed and thrive under the protection and management of Utah Open Lands, Utah Department of Forestry, Fire, and State Lands (UFFSL) and the eight tribes who have inhabited the area. This conservation project was completed through collaboration of these communities with the Utah Division of Indian Affairs and Utah Transit Authority.

Where we stand today, we’re offered a glimpse of what this area must have looked like hundreds or even thousands of years ago. The gift that the conservation easement has offered the community is the opportunity to hold onto and learn from a history that development often erases.

Phragmites australis

As we walk toward the creek, it’s hard to ignore the wall of tall, feathery grass growing along both sides and in some areas, obstructing the stream entirely.

Phragmites australis, an opportunistic invasive reed grass, grows prolifically in disturbed wetlands replacing species that provide habitat and food for birds.

Now that the land has been protected, we can reconnect Corner Canyon Creek’s waters with its floodplain and create space for a diversity of wetland plants again.

Managing Phragmites and other invasive plant species is part of the restoration strategy here and in other wetlands across Utah. Since 2010, the state has actively been working to reduce its cover, restore native wetlands, and improve bird habitat.

Thick wall of Phragmites australis obstructing views of Corner Canyon Creek.

Hambrecht managing Phragmites in the creek.

I spoke with Keith Hambrecht, UFFSL’s Invasive Species Coordinator, about this work. He says about the process:

“It’s difficult to control as it’s a perennial plant. However, there has been a lot of research nationwide, and locally here at Utah State University on how to control it, specifically at the Great Salt Lake wetlands.

One control method is herbicide spraying (necessary to kill the roots of the hardy perennial plant). This will kill the plant itself, but the biomass will need to be removed physically by cutting or burning. This cycle needs to be repeated over several years.As another control method, sometimes cattle are introduced to reduce plant biomass, open up habitat, and contain growth. Introduction of cattle can also improve habitat without being too hands-on in treatments.”

The vast scope of Phragmites control may feel insurmountable. Because Great Salt Lake has receded, freshwater inflows now “feed large pastures of Phragmites” which would otherwise reach the lake and provide more diverse habitat.

However, Hambrecht reiterates the importance of tackling the problem and expresses optimism, noting recent progress. According to Hambrecht, Phragmites cover around Utah Lake has been reduced by 70% since its peak, and waterfowl management areas around Great Salt Lake have seen significant reductions.

While the work that UFFSL and volunteers are doing here today isn’t the end of the line for Phragmites, it does give us the opportunity to access the stream to do the important restoration work we’re here to do today.

As with Great Salt Lake, a wall of Phragmites at Galena Soónkahni is also creating a blockage that keeps freshwater from flowing into Corner Canyon Creek’s floodplain wetlands.

The process of removing this invasive species is no small feat and is something that wetland managers across the state are making substantial strides toward.

Talking with Hambrecht about the management of this invasive species shines a hopeful light on a future where reintroduction of native species, improved biodiversity, and delivering more water to the lake feels within reach.

Morgan Faulkner of UFFSL managing Phragmites along the floodplain.

Collaboration & Community

A close-up of the mud and willows that have been weaved together in a BDA.

While the UFFSL team tackles invasive species control in the area, volunteers and other state partners are hard at work gathering materials to mimic beavers by building BDAs. These structures slow the rate of creek flow during storms, capture sediment, and promote re-wetting of floodplain soils.

Rose Smith shares with the team the importance of the work we’re doing in the creek today. “Beaver currently inhabit and have historically maintained wetlands along the Jordan River,” she says, “crafting dams that create habitat for a variety of wildlife. But many of them have been removed. In their absence, human-made structures can help to provide some of these benefits.”

Currently, Smith says this creek is operating like a big pipe. “It conveys water quickly and efficiently to the Jordan River. However, efficiency is not always the answer when it comes to wildlife habitat and water quality. These structures jump-start natural processes that allow the floodplain to become less pipe-like and more sponge-like.”

It’s through the busy, beaver-like work of our volunteers that our stream restoration days are made possible. I spoke with a few of the volunteers who joined us on this stream restoration day. Each came to Sageland and the event with different experience levels and through different avenues.

Volunteers Abigail Slama-Catron and Candice Clark working on a BDA together.

Abigail Slama-Catron found out about the event through Utah’s Division of Wildlife Resources, and she hopes to work in this field in the future. This was Abigail’s first time building BDAs, and she has a lot of great things to say about her experience. She says, “I actually had no idea what I was going to get into. I just came and was not wearing the right stuff at all, and now here I am, in waders! It was like being a kid again, just weaving, and putting mud and rocks everywhere—it was just really fun.”

Slama-Catron’s experience is not uncommon. A lot of our first-time volunteers come into the project not quite knowing what to expect, but leave with a sense of fulfillment from the work they’ve done. And all of this happens while reconnecting with a piece of childhood wonder.

Other volunteers know exactly what they’re getting into when they join us.

Dave Wallace working on a BDA.

Dave Wallace, a semi-retired CPA who now serves on Sageland Collaborative’s board, joined us at Galena for his fifth stream restoration day. Wallace sought out opportunities in outdoor volunteerism after taking a course in erosion control that opened his eyes to the real impacts that this type of work could have.

While this is Wallace’s first foray into the volunteer opportunities that Sageland offers, he says he would love to get his grandkids involved in a project like the Boreal Toad Project or Utah Pollinator Pursuit.

These offer the opportunity to go on a hike with kids or grandkids, but also gives them the purpose of finding amphibians or butterflies—it makes these hikes even more meaningful.

With a variety of projects that span across seasons, volunteers can easily dip their toes into other projects while waiting for their favorite to kick back up again. That’s how volunteer Candice Clark came to be involved in our stream restoration project.

Clark started off in her volunteer journey last year on the Boreal Toad Project, and after joining as many survey days as she could, she was named our 2022 Boreal Toad Volunteer of the Year.

The Boreal Toad Project and our Riverscape Restoration are both hands-on, in-the-field projects that provide volunteers the chance to interact with species and locations in a way that most people don’t get to. It only makes sense that Clark would make the jump from toads to streams.

Clark compared the two projects that she’s volunteered on, sharing that “stream restoration is a lot more physical, a lot more work.”

“But,” she says, “it’s more rewarding because you can see results right away. Everyone wants immediate gratification.”

This is another common experience in our stream restoration work: the sense of fulfillment from seeing immediate results after hard work in the creek. As you weave willows and layer on mud and rocks to give structure to the BDA, the water upstream of the BDA gradually rises. And by the time you’re done, the difference between the water levels on each side of the BDA can be quite drastic.

Volunteers and state partners posing with their nearly finished BDA.

Sageland Collaborative

As I get to know our hardworking volunteers and partners, there’s another human jumping from conversation to conversation at the preserve.

If you’ve had the chance to meet Sageland Collaborative’s Board Chair Jaimi Butler, you know how delightful it is to chat with her about everything from the Great Salt Lake to birds to farm animals. So when we crossed paths at the restoration event, I couldn’t wait to hear her thoughts on our work at Sageland Collaborative.

Butler says, “Sageland is in this really cool place where they’re using science to help us understand our natural world and its wildlife. I’m just so proud to see all of the partnerships that are being made and all of the data that’s being collected and managed. I’m excited that we’re seeing on-the-ground improvements in habitat, wildlife, and wetlands.”

Volunteers and partners after wrapping up the restoration day.

This collaborative spirit among project partners—namely Utah Open Lands and state agencies—is what led to the protection of the Galena Soónkahni Nature Preserve. Sageland’s team is honored to participate in the ongoing stewardship and restoration work of critical habitat sites like this one.

This work would not be possible without the outstanding support of our community. Thank you to the volunteers and partners who contribute their time and expertise!

Authors: Sierra Hastings & Rose Smith

Photos (aside from archaeological site photos): Sierra Hastings